Support from readers like you keeps The Journal open.

You are visiting us because we have something you value. Independent, unbiased news that tells the truth. Advertising revenue goes some way to support our mission, but this year it has not been enough.

If you've seen value in our reporting, please contribute what you can, so we can continue to produce accurate and meaningful journalism. For everyone who needs it.

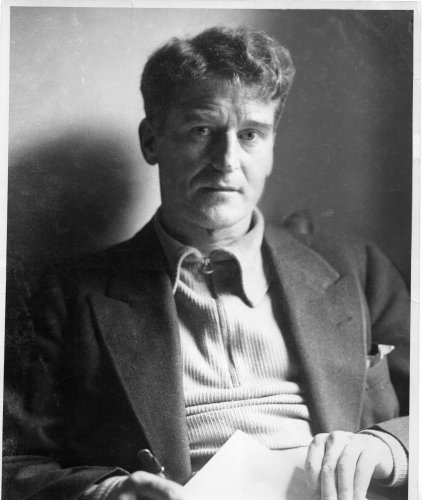

Ernie O'Malley, who interviewed the survivors (Mercier Archive)

Ernie O'Malley, who interviewed the survivors (Mercier Archive) Michael Collins (marked with a cross) leaving Dublin Castle with Kevin O'Higgins and WF Cosgrave after the surrender of anti-Treaty forces in 1922 (Tophams/Topham Picturepoint/Press Association Images)

Michael Collins (marked with a cross) leaving Dublin Castle with Kevin O'Higgins and WF Cosgrave after the surrender of anti-Treaty forces in 1922 (Tophams/Topham Picturepoint/Press Association Images)

have your say